A Cleveland Clinic psychiatrist discusses what the latest research suggests causes bipolar, what the individual experiences, and often effective interventions.

How a Person with Bipolar Disorder Thinks, an Expert Doctor Explains

About the expert:

Stephen Ferber, MD, is a board-certified psychiatrist and the Assistant Director of the Psychiatric Treatment-Resistance Program at Cleveland Clinic. He completed a fellowship in Interventional Neuropsychiatry and Neuromodulation at Massachusetts General Hospital, bringing extensive expertise to the management of treatment-resistant mental health conditions. Dr. Ferber specializes in interventional psychiatry, with a particular focus on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), Ketamine therapy, and Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT). His research has centered on optimizing targeting strategies in TMS, and he is an active member of both the International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation and the Clinical TMS Society.

Data shared by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 40 million people live with bipolar disorder worldwide. Bipolar disorder, formerly referred to as manic-depressive illness, is a mental health condition characterized by extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression).

Stephen Ferber, MD, a board-certified psychiatrist and the assistant director of The Psychiatric Treatment-Resistance Program at Cleveland Clinic, helps to shed light on how a person with bipolar disorder thinks for someone who may be trying understand the emotional and mental challenges that individuals with this condition can face. Dr. Ferber says these mood shifts can deeply influence a person’s thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors, often making their experiences difficult to comprehend for others.

Ahead, Dr. Ferber shares his practiced insights into the inner experiences of individuals with bipolar disorder, as well as treatments and strategies for support.

What is bipolar disorder?

According to Dr. Ferber, “Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric condition that encompasses two main features.” These include episodes of depression and episodes of mania or hypomania.

During depressive episodes, individuals may experience symptoms such as persistent sadness, low energy, and difficulty concentrating. While these episodes resemble those seen in major depressive disorder, what distinguishes bipolar disorder is the occurrence of manic or hypomanic episodes.

Manic episodes are characterized by heightened mood, increased energy, or impulsive behavior, while hypomanic episodes are less severe but share similar characteristics. These episodes can last for days or weeks and are often followed by a return to a baseline emotional state or a transition into depression.

Dr. Ferber explains that the primary goal for doctors is to first manage and reduce the intensity of depressive and manic symptoms when they arise. Once those symptoms are fully addressed, the emphasis moves to minimizing the likelihood of future episodes and supporting long-term emotional stability.

What causes bipolar disorder

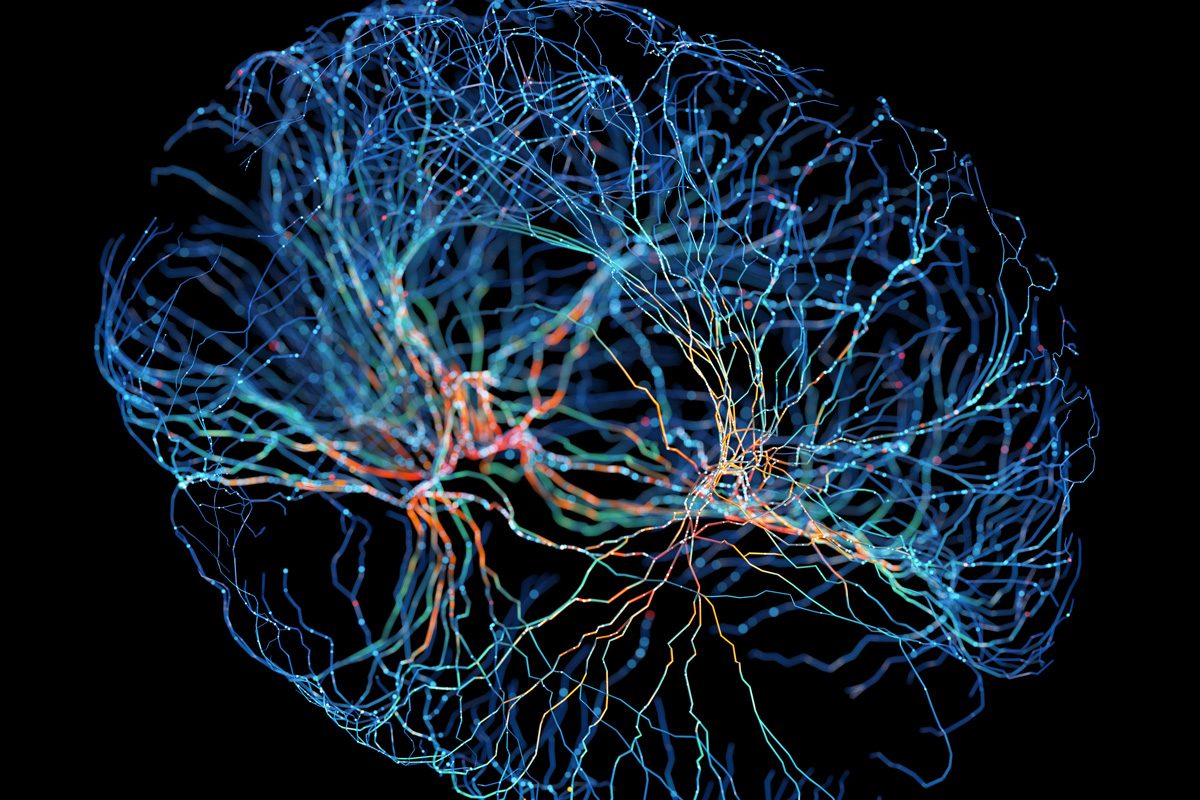

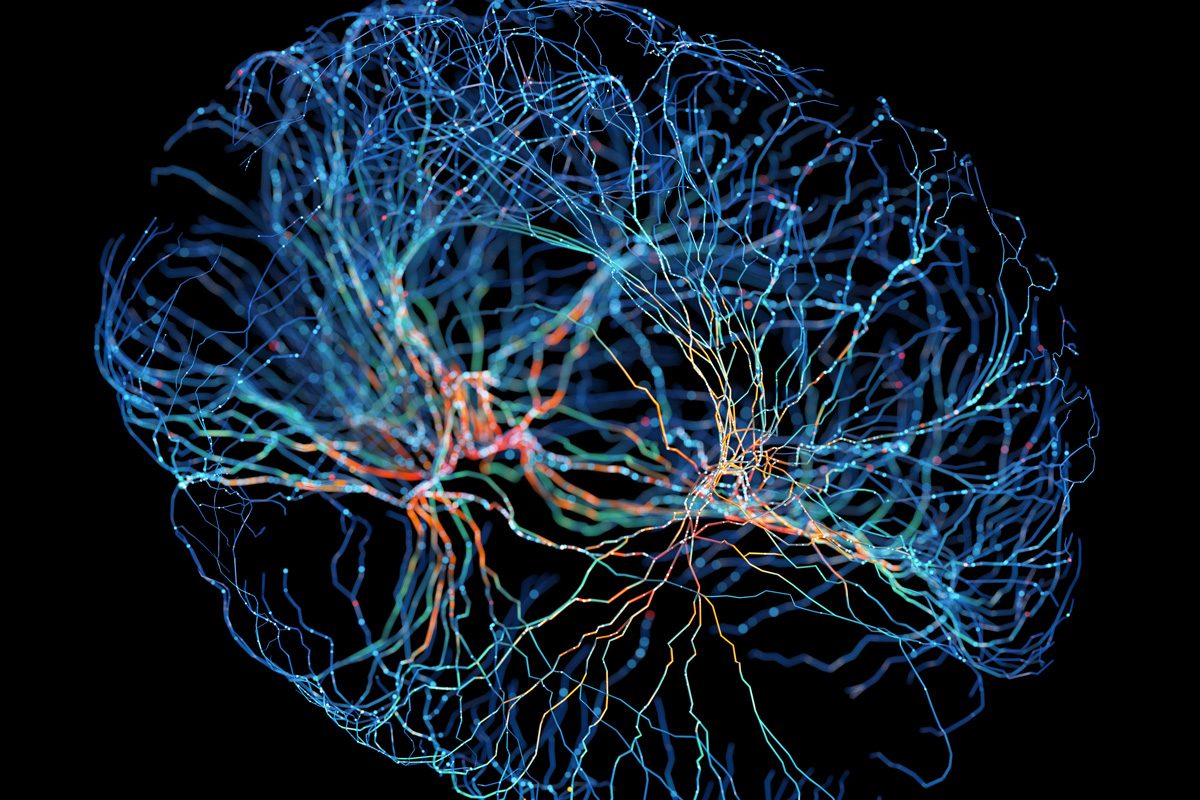

“Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly what causes it,” says Dr. Ferber. “There are varying factors.” Psychiatry as a field is still evolving in its understanding of how the brain and mind interact. “What we’re beginning to understand now is that every psychiatric or mental health condition, including bipolar disorder, is likely caused by a disorder in neural networks,” he explains.

Neural networks refer to regions of the brain that activate or deactivate together. Psychiatric symptoms may arise when these networks are overactive, underactive, firing in improper patterns, or reacting to inappropriate stimuli. Bipolar disorder, like other mental health conditions, involves abnormalities in these networks.

Research indicates irregularities in specific brain regions, including the dorsal anterior cingulate, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and central brainstem structures. These regions are associated with mood regulation and the production of chemicals like serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Dr. Ferber clarifies that while we know these areas and their connections are involved, the precise mechanisms of dysfunction are not yet fully understood.

Types of bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is often classified into two main types: bipolar I and bipolar II. Bipolar I is characterized by severe manic episodes that may require hospitalization, often accompanied by depressive episodes. In contrast, bipolar II involves a pattern of depressive episodes and milder hypomanic episodes that don’t reach the intensity of full mania.

However, the reality is more nuanced than this binary classification suggests.

Dr. Ferber highlights that bipolar disorder exists on a spectrum. At the severe end, symptoms such as risky behavior and prolonged periods without sleep make the condition obvious. On the milder end, symptoms can be subtle and harder to identify, often leading to misdiagnoses like major depressive disorder, which can delay proper treatment.

How a person with bipolar disorder thinks

Dr. Ferber recommends reframing this question to avoid making broad generalizations about people with bipolar disorder. Instead, it’s more accurate to focus on the symptoms individuals may experience.

Bipolar disorder is a complex and highly personal mental health condition, with no two people experiencing it in the same way. Since bipolar disorder is episodic, changes in thinking and behavior often occur during specific episodes, such as mania or depression. These shifts are symptoms of the disorder, not a reflection of the person’s core identity.

Symptoms can range widely, including heightened energy, racing thoughts, and impulsive decision-making during mania, to overwhelming fatigue, hopelessness, and difficulty concentrating during depression.

How a person with bipolar disorder thinks during a manic episode

Dr. Ferber shares some examples of what can occur during a manic episode:

- Elevated or euphoric mood: A manic episode is often considered the opposite of depression. According to Dr. Ferber, “In a manic episode, people will generally have an elevated, if not euphoric mood.” Symptoms of mania typically develop gradually over days or weeks. This slow progression can make it harder to recognize, especially if the onset is subtle.

- Unusually high energy levels: Individuals may experience a surge in energy, often undertaking numerous tasks at once. This can include starting new projects, cleaning, or reorganizing their home or apartment.

- Grandiose or atypical thoughts: People in a manic state may exhibit behaviors that are out of character for them. Dr. Ferber explains, “One of the hallmarks is engaging in behaviors that are out of the norm for them, whether it’s spending a lot of money, gambling, driving fast, or engaging in recreational activities like drug use that they wouldn’t normally do.”

- Hypomanic episodes: Milder forms of mania, known as hypomanic episodes, may be less noticeable. “It may just look like the person is being ultra-productive at work, maybe they’re sleeping just a few hours less, so it might not be particularly noticeable,” he adds.

How a person with bipolar disorder thinks during a depressive episode

Dr. Ferber explains that depressive episodes involve a variety of symptoms that can disrupt daily life, including:

- Periods of low mood: Feeling persistently down, sad, or emotionally drained.

- Anhedonia: The inability to enjoy activities that once brought happiness or pleasure.

- Low energy levels: Struggling to find the motivation or strength for everyday tasks.

- Difficulty sleeping: Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or experiencing restless, unsatisfying sleep.

- Cognitive challenges: Inability to concentrate, focus, or plan, which can make decision-making and problem-solving feel overwhelming.

- Feelings of guilt: Often paired with self-blame or a persistent sense of worthlessness.

- Feelings of hopelessness: A deep sense that circumstances will never improve.

- Suicidal thoughts: At its worst, thoughts of not wanting to be alive anymore, which require immediate medical professional attention.

What most people don’t understand about bipolar disorder

A common misunderstanding about bipolar disorder is confusing it with other mental health conditions that share similar symptoms. For example, “conditions that often get labeled as bipolar disorder, but aren’t, include ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and Borderline Personality Disorder,” explains Dr. Ferber. “Borderline Personality Disorder, in particular, has a lot of symptom overlap with bipolar disorder but represents a more chronic course and is less episodic.”

Another source of misinformation is the belief that bipolar disorder can be completely cured. Many assume it’s comparable to treating pneumonia—take antibiotics, recover, and it’s gone. However, this isn’t the case. Bipolar disorder is best understood as a chronic condition, similar to Crohn’s disease. While treatments such as medication and therapy can lead to extended periods of symptom-free living, the underlying condition persists and requires ongoing management.

He adds: “Even when a person isn’t actively symptomatic, they will always have a non-zero risk of experiencing another episode of depression or mania.”

How bipolar disorder is treated

“The mainstays of treatment for bipolar disorder [are] interventional options, medications, and various types of psychotherapy,” states Dr. Ferber. Treatment strategies depend on the individual’s current state—whether they are in a manic or depressive episode—and aim to address immediate symptoms while preventing future relapses.

Acute manic episodes

If someone is experiencing an acute manic episode, meaning they are actively in the middle of one, treatment typically begins with mood stabilizers. These first-line treatments include medications such as lithium, valproic acid, and oxcarbazepine.

Bipolar depression

Treating bipolar depression can be more challenging. “There are only five FDA-approved medications indicated for that specifically,” says Dr. Ferber. These include cariprazine, lurasidone, lumateperone, quetiapine, and a combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine.

Long-term management

Once the acute symptoms are addressed, the focus shifts to minimizing the risk of relapse. This involves ongoing mood stabilization therapy. Lithium, for example, is a widely used option that helps reduce the likelihood of both manic and depressive episodes.

“Ideally, we want to have people on the fewest number of medications at the lowest dose possible that they need to be happy and healthy,” he emphasizes.

Interventional approaches

While medications are a significant component of bipolar disorder treatment, they aren’t the only option. “My area of specialization is what’s called interventional psychiatry, which is basically all of the non-medication, non-therapy options for various treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders,” says Dr. Ferber. The three main interventional approaches include:

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): Effective for both treating and preventing manic and depressive episodes.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS): Primarily used for bipolar depression. Although not FDA-approved for this specific use, there is growing evidence of its benefits, though insurance approval can be a hurdle.

- Ketamine (intranasal spray or intravenous infusion): Another promising treatment for bipolar depression, though it faces similar insurance challenges to TMS.

Dr. Ferber also notes that when it comes to treating bipolar disorder or treatment-resistant depression, medications often fall short. “If we’re looking at this from a pure numbers game, medications don’t work great,” he shares, noting that many medications have a success rate of only about one in three. For this reason, he strongly encourages patients to explore non-medication options for bipolar disorder including ECT, TMS, and ketamine therapy. However, access can be a significant challenge as many of these treatments are primarily available in large academic health systems located in major metropolitan areas making them inaccessible for some patients.

“Our goal is remission, meaning that we want patients to have a complete absence of symptoms by the time that they’re done with their treatment,” he says.”If that isn’t achieved, I would urge patients and family and referring providers to keep trying and to not settle for anything less than that.”

How to support people with bipolar disorder

Supporting a loved one with bipolar disorder involves patience, understanding, and teamwork. Start by being present and encouraging them to stay committed to their treatment plan, even when they feel better and might think they no longer need medication. Skipping medication can increase the risk of relapse, and while the side effects can be challenging, consistent treatment is essential for remission.

To help combat feelings of isolation that often accompany depression, consider participating in activities together, such as exercise, meditation, or relaxation techniques. These shared experiences can provide emotional support and promote a sense of connection. When welcomed by the individual, family involvement can be a key part of recovery. And it’s not just up to family and friends to support the patient. The medical team plays an important role in optimizing treatment plans to minimize side effects and reduce the risk of relapse, Dr. Ferber concludes.

For daily wellness updates, subscribe to The Healthy by Reader’s Digest newsletter and follow The Healthy on Facebook and Instagram. Keep reading: